In the last two blogs, we discussed what a cardiomyopathy is, paying particular attention to the categories of dilated and hypertrophic. This week we’ll complete our review of cardiomyopathies with a look at the category of restrictive.

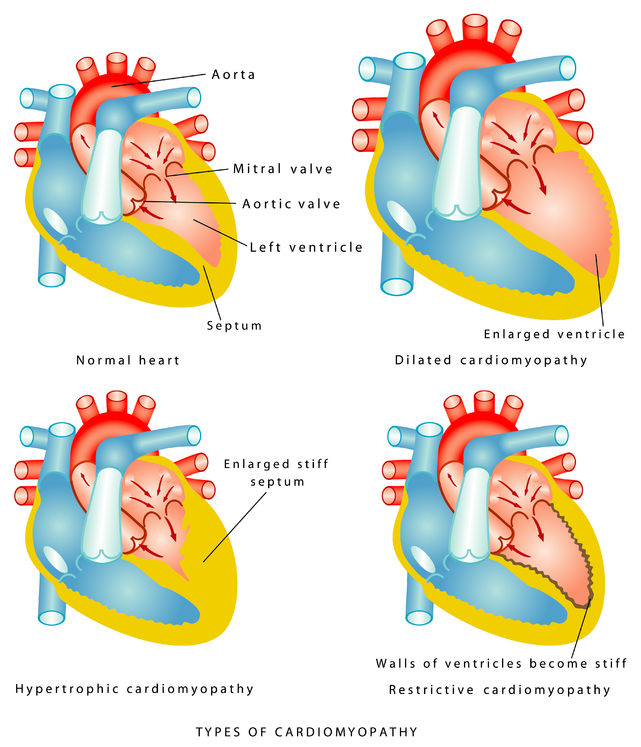

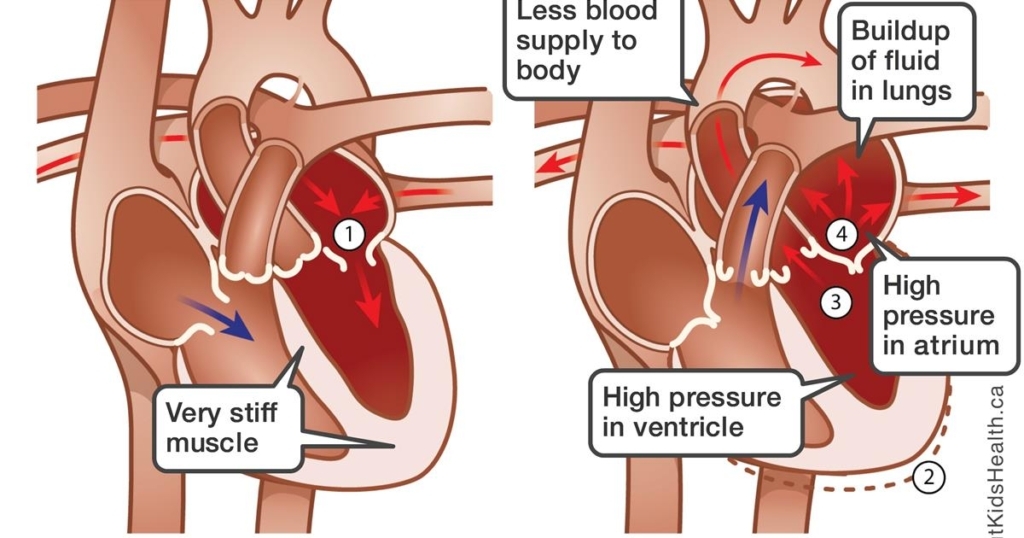

While dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies are defined by anatomic features (an enlarged heart chamber in the first and thickened ventricular walls in the second), restrictive cardiomyopathy is defined by its physiology, i.e. how the heart functions. In a restrictive cardiomyopathy, the heart contracts just fine (systolic function is intact), but the walls don’t relax as well as they should (diastolic function is abnormal).

Another distinction between the dilated, hypertrophic and restrictive cardiomyopathies is that the first two generally affect the left ventricle exclusively, whereas the processes that lead to restriction usually affect the right ventricle as well as the left. As the image below indicates (unfortunately it only illustrates the left-sided issues), fluid retention is a prominent feature. In the left ventricle, it causes shortness of breath as fluid is retained in the lungs; in the right ventricle it leads to swelling and bloating as fluid is retained in the body tissues.

There are many potential causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy. These include several rare genetic disorders—so-called storage diseases—that lead to deposition of abnormal molecules in tissues throughout the body, including the heart, which leads to increased stiffness. The most common cause is idiopathic (which is a fancy word for medical science not being able to determine the cause!). Chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cancers can lead to scarring in the heart and therefore restriction. The three most prevalent treatable causes are amyloidosis, hemochromatosis and sarcoidosis.

In amyloidosis—which we increasingly recognize is more common than we thought—amyloid proteins deposit in the heart and lead to restriction. This can be due to a genetic abnormality, a concomitant of aging, or related to a blood cancer called “multiple myeloma.” Hemochromatosis is due to iron overload and is also usually caused by a genetic abnormality, but can also be triggered by receiving too much iron in transfusions for anemia. Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disorder that is characterized by the deposition of nodules (called granulomas) in many organs, including the heart. Although it has been studied extensively, the exact cause of sarcoidosis has never been conclusively determined.

Most of the time, a restrictive cardiomyopathy is diagnosed indirectly, when we find a patient has CHF with normal systolic function. It requires some extra investigation to discover the patient doesn’t have “run of the mill” diastolic CHF, but an actual restrictive cardiomyopathy. Tests that are routinely done in patients with CHF include an EKG and an echocardiogram and there are features of these two tests that might suggest a diagnosis of amyloidosis. A cardiac MRI can be helpful. Blood tests to look for iron overload may be done in the appropriate clinical situation. Sarcoidosis is often known prior to its cardiac involvement, as the skin and lungs are the most prominent organs that are involved in this disease.

The treatment of restrictive cardiomyopathy has both a general component (salt restriction and diuretics for the CHF) and a component specific to the cause. Hemochromatosis is treated by limiting dietary iron, as well as by phlebotomy (plain old-fashioned blood-letting—but done in a controlled and sterile setting), which is a way to remove iron from the body. Sarcoidosis is usually treated with steroids, as well as other anti-inflammatory agents. Amyloidosis used to be untreatable, but there are new drugs (and others in the testing stage) that allow treatment of hereditary and age-related versions of this disease. For patients who have amyloid caused by multiple myeloma, the therapy is treating the cancer.

We have spent a good deal of time in these last three blogs discussing cardiomyopathies. The category is broad, including several different types, each of which has a multitude of causes (at least for the dilated and restrictive varieties). Compared to when I learned about these cardiac problems in medical school in the 1980s, we now have many more options for treatment, giving hope to patients who suffer from these disorders.

Greg Koshkarian, MD, FACC